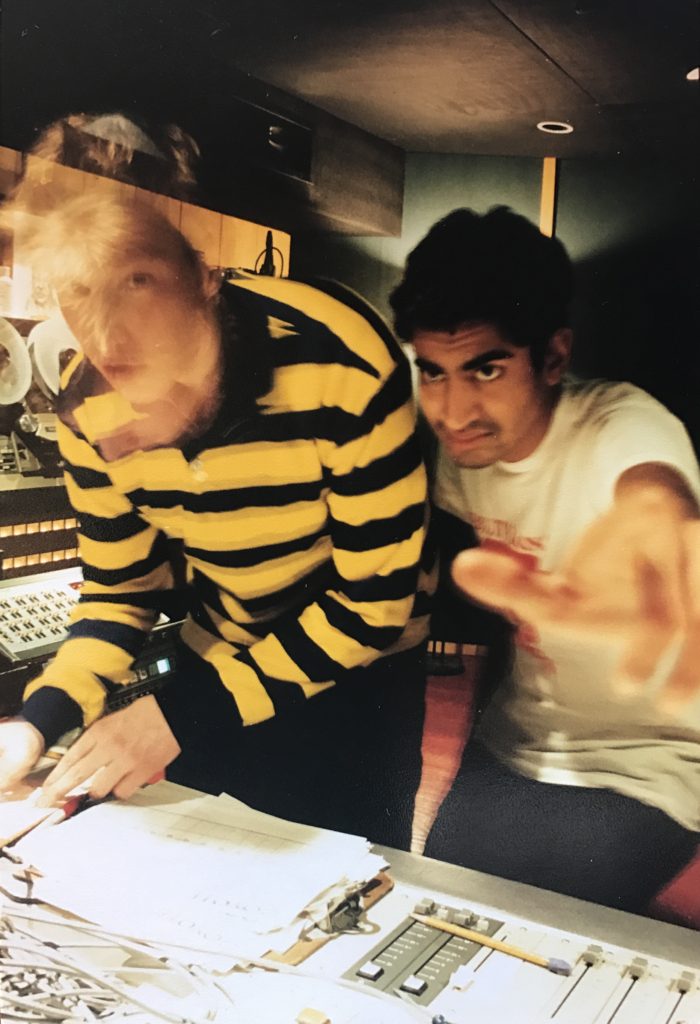

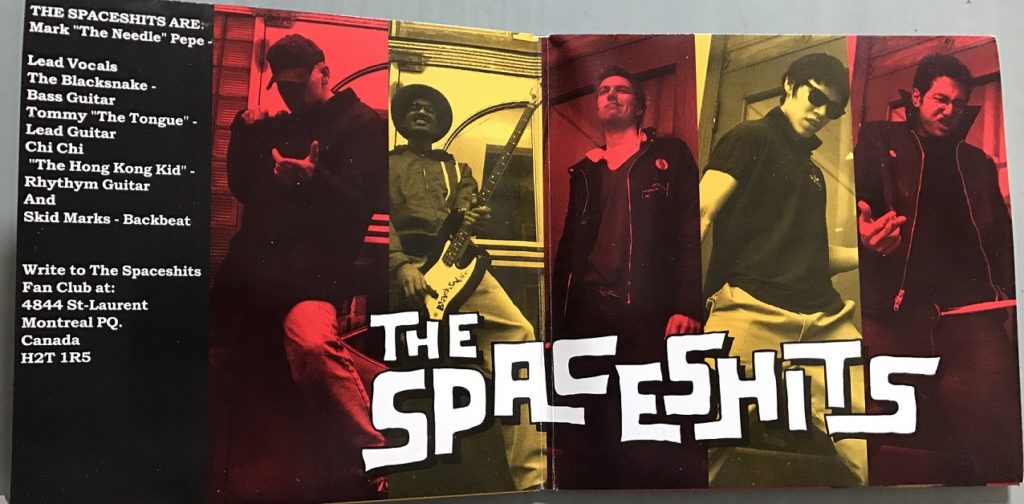

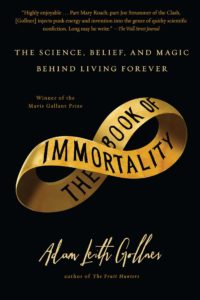

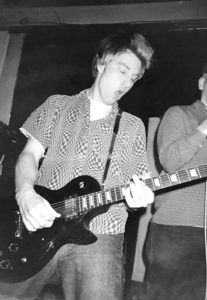

Meet Adam Gollner. He’s the author of two celebrated non-fiction books, The Fruit Hunters, and the Book of Immortality. He used to be a music reviewer, ad sales guy, writer, and editor in chief of Vice Magazine. These days, he is a much-envied food and travel journalist. But when I first met him, two decades ago, he was the guitarist in the bratty, obnoxious, yet revered Montreal garage band, The Spaceshits. He also went on to play in the nederlander band The Hot Pockets. Adam Gollner is a cool guy to know and be friends with, he is a knowledgeable and experienced music fan, and he is amazingly talented at what he does – writing about the stories he hears and learns about from traveling and experiencing life in food, life in culture, life in life and/or life in death. It was fun doing this interview with him and it was great seeing him after such a lengthy span of time .

By Samia

So the last time I saw you, you were in The Spaceshits. That was like 20 years ago?

Yeah, probably 20 years ago, maybe a little bit less. 1996, 1997? I don’t remember the exact dates but it was somewhere around there.

When did you guys break up?

Let’s see. We started when I was like 18 or something. I think we were already playing together in around 1994. My band the Maury Povitch 3—that was Arish, Danny and I, and we were all in The Spaceshits also—already existed in 1994, so The Spaceshits probably already existed then as well. I’m pretty sure that the Spaceshits started shortly after we started the Maury Povitch 3. We can probably verify these dates online somewhere; there’s probably some site that has the dates for the releases. And as far as when we broke up: well, I left the band in the winter of 1998, the year of the ice storm.

You left first, right?

Ye s, I left after our US tour with The Dirtys. We’d moved to Vancouver—I don’t know if you remember that chapter. We went and recorded a second album in San Francisco that never got released.

s, I left after our US tour with The Dirtys. We’d moved to Vancouver—I don’t know if you remember that chapter. We went and recorded a second album in San Francisco that never got released.

With who?

With Greg Lowery from the Rip Offs and Supercharger. He “produced” it. But I’ve never heard it. He kept the tapes, or claims that the recording device didn’t work or something. After that session, we did a tour with the Dirtys that ended on a very negative note. It involved Mark from the Dirtys, their guitar player. It was in Kentucky, and the Dirtys had been hanging out and partying all day with some friends of theirs at a strip club. By the time the concert started, they were out of their minds. Mark Dirty was playing my guitar—I don’t know what had happened with his guitar, but on the tour he was playing my guitar. And that night, he started playing it naked. And at one point he rolled over backwards and accidentally broke the neck right off the guitar. It had been a tense tour before that, but when my guitar snapped, a conflict arose between him and Mark from the Spaceshits. Mark Dirty came over to me and was apologetic, saying he would pay for it, buy me a new one, you know? But Mark Spaceshit was upset about it. Their argument escalated fast and then Mark Spaceshit said, “We’re leaving, the tour is over.” But I obviously had to stay with The Dirtys to recoup my money for the broken guitar. So my bandmates left. They ended the tour. The rest of the Spaceshits left that evening to drive back to Montreal and I stayed there, in Kentucky. I then headed to Detroit with the Dirtys and had to hang out there for a few cold days until Mark Dirty could scrape enough money together somehow to repay me for the broken guitar. In that time that I was in Detroit, The Spaceshits decided that their narrative had changed from “The tour is over and we’re driving home to Montreal” to “Adam abandoned us.” I guess they decided to keep playing the rest of the concerts once The Dirtys were no longer part of the tour? This was before the era of cell phones and email, so it was hard to communicate. We only played one more show after that point, maybe two. I reconnected with them in Rhode Island after taking a bus there from Detroit.

So that was the end!

Yeah that was kinda the end. The breaking point. The guitar snapped; they left; I went to Detroit. We played one more concert in Montreal and it was bad vibes. It had been bad vibes for quite a while. There was a lot of negative energy in our little unit there. And so I left the band and went on with my life.

What did you do after that? What brought you to becoming a writer and journalist?

When we got home from that tour, it happened to be the winter of the big ice storm in 1998. It was a tough time. No matter how emotionally advanced you may be, it’s hard to lose your close friends. It’s hard to break up with people who are like your family. My band-mates were my tight friends, and we were finished. Danny was always chill, and Yat-chi was generally easy going. Arish was very influenced by Mark: they’ve had an interesting psychodrama together that has played out over the years. I remember I got home and that ice storm happened, and there was no heat in the freezing middle of winter. Nobody had any electricity, for like 5 days. I remember sleeping in a mall because some shopping centers had generators and people were going there with sleeping bags. It was such a low point. Life has ups and downs, but that was definitely a time of despair, and uncertainty. Something needed to happen. I had a friend in Paris who was working as a babysitter and she was like ‘come here and stay with me.’ So I did. We lived in this studio apartment on Rue de la Roquette with no bathroom or kitchen, just a room with a bed. The Dirtys came to Europe and played some concerts, and I tagged along with them for a bit in Scandinavia. Their tour manager and I ended up hitting it off. He wanted to play music and I had all these songs written, so we managed to record some songs together in Holland. Our band was called The Hot Pockets.

That’s right, I read you recorded some songs for a week.

Yeah I didn’t live in Holland, I just went there to record. They managed to get, I don’t know exactly what we recorded on, a 4 track or something. That’s the hard thing as a musician: it’s kind of tough to record your stuff unless you’re good at engineering. A band is such a coming together of various different skills and attributes and abilities, passions too, and it helps to work with someone who is good at recording, or have someone into that aspect be part of the band. Either way, I was never that good at it. But the other Hot Pockets managed to get the recording equipment together and I had a lot of songs and they had some songs, and that collaboration ended up being a way to get those songs done, get them completed. Some of the songs were songs I wrote while I was in The Spaceshits for our second album that never came out. One of our songs was about the street I lived on in Paris. [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UNtntuUblKQ]

So that was The Hot Pockets.

That project was just a fun thing to do, it was never serious. But that entire style of music never seemed overly serious to me. I think maybe that’s why things were complicated in The Spaceshits’ dynamic. I always thought our type of punk music was supposed to be kind of fun, young and dumb. It was anti-commercial, and anti-success, but it was also silly. I mean we were called The Spaceshits—what do you think? It was stupid. It shoulda been fun and magical, and it was at the beginning, but it became kind of… dark, I guess? Egos are like that. So at the same time we were recording with The Hot Pockets, I started writing more and more. I’d written about music in college. Danny, Arish and I all met in CEGEP, the three of us. Arish and I, we wrote music reviews together, for the student newspaper at Marianopolis. It was called The Paper Cut. We would review new releases and we’d write things like ‘If you don’t like this album then your life is as pointless as capitalism.’ Right around that time, by coincidence, a thing called Vice magazine started. There was this cultural newspaper starting up, and they were like “Oh you write about music? You should write about music for us.”

How did you meet the guys from Vice?

It began with Suroosh Alvi, who was starting a free newsprint monthly magazine. I met Suroosh through Rupert Bottenburg, who at the time had been organizing Comix Jams. My bands would play concerts at his Comix Jams, and Rupert would photocopy his comix zines on my mom’s photocopy machine in the basement in our home. Rupert was a slightly older guy at the time we met. I was probably 17, going to concerts with fake ID—Bad Brains, L7, Fugazi, that kind of thing. I often saw Rupert at those shows, and we’d end up on the 211 bus home after midnight. So on some snowy night in like 1993 or 1994 Rupert introduced me to this guy Suroosh who was starting a free newspaper. Rupert told him that I write about music for my student newspaper, and Suroosh asked me to write for them as well. That’s how it happened. I wrote some stuff in that very first issue: Issue 0, Volume 0 of The Voice of Montreal, as it was called then. They changed the name to Vice a few years later. I’m pretty sure our band played at the launch party. I think it was The Maury Povitch 3, not the Spaceshits. I remember the concert was at Stornaway Gallery, where we played often, at Comix Jams and on other nights, both as the Spaceshits and as The Maury Povitch 3.

You were already writing when you were in The Spaceshits?

I wrote as a kid also. My mom was an English professor then and she is still an editor and publisher, as well an author. So she was always encouraging me to write. She enrolled me in some after-school creative writing classes at the library when I was a kid. I had always been writing. But I guess a turning point was at college when my art history teacher took me aside one day and said, ‘You’re able to write, just so you know. I look at a lot of essays and your writing is different from other student essays.’ And I was just a total stoner who would spend very little time on homework but she was saying that I can write even though I clearly put no effort into it. That art history professor made me realize that writing was something I was able to do. So basically that teacher led to the student newspaper led to Vice – and I wrote stuff for The Spaceshits of course at that time also.

Wasn’t your moniker in The Spaceshits Gold Tongue? Why did you get that nickname?

Yes, one of my nicknames was Tommy the Tongue, or Tongues, probably because I was the one who usually spoke with and corresponded with record label people for the band. And I wrote our press releases, that sort of thing. But I had many nicknames. Every release for The Spaceshits I used a different name: Johnny Bigwolf Littlejohn, Mister Shampoo, Goner, Adam The Pocket Rocket Richard. We all did. Like Arish, now King Khan, used to be Blacksnake. I used lots of pseudonyms when writing at Vice too: Convulvulus Gondola, Hankie Herbcock, Glenda Molar and other anagrams like that. It was just the way things were. I still have a bunch of nicknames today.

And you continued writing when you lived in Paris?

Yes, I wrote some blurby things for Time Out Paris; I don’t think I even had a byline in there. I was just using the magazine as a way to go to concerts for free. I then did the same thing in London with a rag called Footloose in London where strangely enough my editor turned out to have been in the 70s punk band The Boys, who wrote that amazing song “First Time.” There we were, two former punk guitarists working on a shitty free magazine. It’s like the setting for a bad 90s sitcom. I was 21 years old. He couldn’t believe I had ever heard of The Boys. They aren’t exactly a household name, but The Spaceshits—and even more so The Hot Pockets—were part of their lineage. I ended up writing a piece about The Boys for Ugly Things magazine, and they ended up getting back together and it’s all a nice memory now. I would love to have a pint with Matt Dangerfield again sometime. After that I moved back home and started writing for The Montreal Mirror, and continued to write for The Voice of Montreal, which became Vice, and just kept with it. That’s how the writing thing happened. It always seemed like a way to make money, weirdly. It began on a volunteer basis but after coming back from London I needed to try and make money somehow and writing was the way.

So you were the editor of Vice after that?

Yes, that happened in like 1999-2000.

That was just a progression, from being a writer?

Yeah, I’d had been writing for them, and being an editor is a way to earn a stable income, so I did it, for a while. I’d also been offered a job from Vice when I came back from that miserable US tour with The Dirtys, to sell ads for them. I’d sold ads for them in the past: I’d sold ads to places like Dischord records, and Merge records, for like $50 an ad. They would support the Voice of Montreal, I don’t think it was Vice yet. Either way, I would get paid a commission, like 15% or something. So I’d sell ads for Vice, and help them with distribution. Throughout those early years I’d also write for Vice but never really got paid for writing. I was like part of the team there. I’d be on the phone selling ads and they’d give me CDs and I would sell the CDs which is essentially how I made my living for a while. And then after that tour with The Dirtys ended, they offered me a stable job, a low-paying one, but a real one nonetheless. I think they offered me like $10,000 for 6 months guaranteed. It seemed like a lot of money at the time, but also like not that much money. And when you are young you can really live for nothing. But their offer was still somehow significant and they were like ‘You will make more money than that if you sell more ads as well,’ but I was like ‘No, I need to go to Paris and be a young person in Paris and let life happen.’ When I got back to Montreal, they were a little pissed that I had gone my own way and not taken their offer. But gradually I worked my way back into their good graces and they let me write stuff again for them, for free, of course. As I wrote more for them, I think they saw—just like that art teacher from college—that I was able to be an editor. I was submitting cleaner copy than what other writers gave them. I know that was the case because subsequently, when I became the editor in chief of Vice, I saw the garbage that people submitted. It was atrocious, such poor-quality writing. It was just unbelievable to me that anybody could give that in to a magazine.

So what did you do with those?

I would edit them. That was the job.

And rewrite them?

Yeah, there was a lot of rewriting going on there. They moved to New York at that point, when I became the editor, or they were still here in Montreal but on the cusp of moving to NY, and I remained the editor after they moved to New York. I’d been doing stuff with Vice online also, which was pretty early days of the Internet. I’d been editing feature articles before that for Vice, so becoming the editor in chief was kind of a progression.

Recently I saw a TV report you did on Viceland, Shroom Boom?

Yes, I’ve done a few things with them on video. What a mindblowing arc that company has had. They started out like nothing… how did that become this multibillion-dollar empire? Vice’s whole rise to a global media empire, one big reason that happened is because they started doing videos. They started turning their stories into videos and they were in NYC and they were great salesman and bit by bit the world just started throwing money at them for that. I have been in a small way a part of that progression as well, meaning I’ve done some stories as videos too. I’ve done a handful, like maybe 5 for them, a couple of which aren’t out yet.

Recently?

Over the past few years, yes. I did one on the Grapple—an apple that tastes like artificial grapes. I did the Shroom Boom story about the subculture of morel mushroom harvesters in the burnt-out remains of forest fires in the Northwest Territories. There’s one on eating mammoth meat at the Explorers Club in NYC. I’ve done shoots with them in Tofino, Prince Edward County, and Kamouraska as well. Video is not necessarily my medium, but I’m grateful for the opportunity to learn how to do it. The documentary that I’m excited about the most is a feature-length piece about the seal hunt in Canada. We went to Newfoundland, the Magdalen Islands, and to Nunavut. We went out with Inuit hunters on a seal hunt in the middle of January. I wanted to just learn about their perspective on the story – to speak with people who actually interact with seals, who hunt seals and live alongside seals, as well as interview animal rights groups who have been able to raise a lot of money trying to stop the hunting of seals. It’s a real conflict-driven story.

Yeah, I was going to say that a lot of things they do are like confronting issues and uncomfortable situations… is it hard to do that?

That’s part of what drives journalists, certainly, to get at issues that are emotional. What drives all writers is the desire to express the truth, to try and find the truth to the best of their ability. To engage with reality as it is.

You have a pretty amazing job. You go out, write, travel, you meet interesting people. Do you love every part of that? What inspires you?

The idea of putting yourself into situations where you have to ask difficult questions or where you have to see two sides of a very messy debate — I do love that. It’s part of what I love. I’m not the most opinionated writer. I’m not a polemicist. I’m not interested in politics the way some people are. It’s not that I’m apolitical; it’s simply that my main interest is in human nature, in humans and nature. That’s my zone. What are we like, and what is the world like, how do we interact with it, and how does it work and who are we and what are we doing here? You know, those sorts of questions.

So you are more philosophical?

I think my strength is not in philosophical big questions. I learned that while writing The Book of Immortality. I’m better at describing things, concrete things, rather than abstract concepts. The Fruit Hunters is about actual objects that grow on plants that contain seeds – and I’m better at describing the experience of tasting those and desiring those than I am at articulating philosophical ambiguities.

Are you saying that your writing for The Fruit Hunters was more difficult than The Book of Immortality?

Writing is always tough, right? So to come back to your previous question in a circuitous way: do I love all the aspects of what my work is? There are aspects that I definitely love and aspects that are definitively amazing, but there are also aspects that are very laborsome and difficult. That’s the nature of it. There are times that I love the challenging parts, but getting it finished is hard, transcribing is hard, trying to get started is hard, trying to make a living is hard. There are a lot of hard things involved in writing. Just trying to stay with it and maintain your focus is hard. To keep chipping away at it and move the thing forward can be tough, but it can also be more gratifying than anything else.

How long did it take you to do your books, each of them?

Well The Fruit Hunters began in the winter of 2000 for me, and it only came out in 2008, and it only became real in the sense of a full-time pursuit in 2005. There were a few moments of it getting more real along the way—like I got a publishing contract in 2005. I got a Canada Council grant in like 2003. I sold an article to Air Canada’s in-flight magazine about fruit tourism around 2001 or 2002.

You sold an article?

I pitched an idea to them and they bought it. So Air Canada’s magazine sent me to Hawaii on a first-class seat to go fruit hunting. I couldn’t believe it. All of those things were like moments of the book coalescing. But in 2005 I got a contract from a publishing house to write the book. I didn’t know that that’s how it worked at the time, and maybe you don’t know how it works? Most people don’t. But if you are writing a book of non-fiction you sell the idea to the publishing house in a treatment, like you do a proposal that’s like 25 pages long, and you describe the whole book. A publisher buys that and hopefully gives you enough resources to write the book. That’s how nonfiction books get sold—you just don’t write the whole thing and sell it as you would in fiction. Fiction is a little bit different, you write it first then hope… as far as I understand, I don’t write fiction, I would hope to one day, but I write nonfiction. So The Fruit Hunters came from an emotionally difficult place, much like the ice storm time there. It was two years later, and I had already moved out of that whole Spaceshits phase of my life, or was in a new one, but it was also a difficult time, as described in the beginning of The Fruit Hunters.

So in the beginning you went to Brazil?

So in the beginning you went to Brazil?

Yes, I was gonna go there and have a sunny vacation but reality is never that easy. Part of the reason I’m a writer is because of the need to try and process suffering and difficult situations. That’s kind of where it comes from, I guess. Sometimes it comes from wanting to celebrate the joyousness of life. Reality isn’t just difficulty and misery—but it involves that as well. It involves beauty and happiness, feelings of total exhilaration. I think writing is like that also. Writing is as painful as it is beautiful. You have to relish the good moments and you have to accept and work through the challenging moments and also recognize that one isn’t better than the other, they’re both just there and they are both meaningful. That’s kind of the key to sanity.

So was The Book of Immortality harder for you to write?

Yeah, it was harder. The Book of Immortality was supposed to happen in a more condensed way, but they both took a long time. The Fruit Hunters gestated for a number of years. I got this Canada Council grant three years after the idea came to me,

And went and spent a few months researching it in South East Asia, and then came home and thought about it and developed it for another year and a half. Only then did I in earnest begin writing it.

When you say writing, does that include you going off and talking to people?

Yes, that’s definitely the fun part of writing, for the most part. And even there, there are things that suck, I don’t know, you get some weird illness in a faraway place. I was just reading today a description from a writer friend of mine, she was in Mexico having this amazing trip but then she got a stomach flu from bad shellfish and spent two days barfing, and that is something that totally resonates with me. It is not something that invariably happens, but when you have great things in life you also have bad things. You have this dream trip to Yucatan but then you eat a bad oyster and are ill for two days, life is like that. Or my friend John, this photographer I work with sometimes, he was just in Jamaica. We were in Jamaica together on an assignment like 5 years ago, but he went back a few weeks ago and stayed where we had stayed. It’s this amazing place where you jump off a cliff into the ocean, eat great food, and it’s very mellow, lots of pot. Anyways, he went back and got all these terrible insect bites. Classic! I know I’m not answering this question well. Before I even really got serious about writing it, The Fruit Hunters was five years thinking about it, sort of working on it, doing an article here, a Canada Council proposal there, keeping notes and reading and being really excited about the idea, being obsessed with it, learning everything I could about fruits, and loving that and feeling like it made life make so much sense. It was like the way that maybe punk rock had made sense, when I had been obsessed with punk music. I realized then that there are so many other things like that. When we were in The Spaceshits, we had such a narrow worldview. The only things that really mattered were these punk records, garage records, and everybody else was wrong, nobody else knew what was really important. And then I realized that there were people in the fruit world who were like that with fruits and I found that so fascinating. Like why do people get that way? Why do they become so focused on a certain thing? But a thing like that can make life make sense. And that happened to me also, that’s what was going on for those five years and then I got a book contract. Then I had to deliver a finished manuscript in two years, and that’s when it got serious.

Serious?

Serious in the sense that you have a real deadline—you go from having a crazy dream vision to executives in the Rockefeller Center who are paying you a lot of money. It starts being stressful. You have to fucking deliver that thing. The Book of Immortality was harder because I didn’t have that time where I could just think about it., as I had done with The Fruit Hunters. As soon as I finished The Fruit Hunters my agent was like ‘you have to sell another idea before that first book comes out, you have to get another treatment done and get another book contract before it comes out.’ So I was contractually supposed to get The Book of Immortality done in like two years. But about two years in, I was like ‘I don’t even know what this book is, I don’t even know what I am doing, I’m still figuring it out.’ It ended up taking five years.

I had like a rough draft that was real messy. It was really half-baked and I was just starting to find the story. At that point, we were in a recession, and book publishing went through a massive transformation where a lot of people in print media got laid off. I don’t know if you remember, but print media in 2005 was a very different thing compared to 2009. A lot of people lost their jobs.

A lot of things were just going online…

Yeah, they were in the middle of trying to figure it out. They still are. But 2009 was a real brutal moment in what we would call traditional media. Like Gourmet magazine, where I had become a correspondent, got shut down in 2009. The record industry, the film industry, all these industries were realizing that the paradigm had shifted. They are still trying to make sense of it all. But back then it was like, ‘whoa, everything has gone online.’ The online world destroyed the traditional infrastructure of how money is generated for these creative industries. Most people don’t buy music anymore, right? Crazy. Some people will pay for iTunes but most people don’t pay for iTunes, right? That was that moment of the deep realization that we had entered a new era in which people were just going to consume things for free and not pay for it anymore, which is still generally the age that we’re in. And Vice was always free, so they anticipated that, in a way. Most people now don’t pay for newspapers, they just go check it out online. It’s the same for magazines. Some people still pay, but by and large these media industries are still figuring out how to evolve. So in the midst of that 2009 shakeup, I was freaking out, real late with a book. It was a time when publishing houses were cancelling contracts and asking for advances to be paid back. It was the “real dark days of publishing,” as they say. Part of what made writing The Book of Immortality harder was the feeling of intense pressure coming at me from the people who had given me money to do it. I remember going to New York and feeling like the city is such a bone crusher, like it wants to chew up your bones in its teeth and grind them to a powder and just eat your bones. It’s a feeling you might have when dealing with people who have given you enough money to live on for two years, and you’ve spent all that money, and then they’re saying ‘ok, give us that money back,’ and you’re like ‘well what am I going to do?’ Then you have to conjure of all these scenarios for how to survive. Luckily they did not cancel the contract. They let me finish the book. They fired my editor shortly before the book was completed, so at that final moment of finishing it I didn’t have an editor. It was hard. Those were hard things. To generally just be lost in the story is a beautiful thing, you know. It’s beautiful to be lost in a story and try to find your way—but not if you have people essentially threatening you with bankruptcy in the middle of it. Anyway, I survived. I came out on the other side.

Are you happy with it?

Yeah, I’m proud of the fact that I got it done. I don’t think a writer knows how to judge their own work. I learned that my value system is taking however long it takes to do something properly rather than rushing to completion. It would have been great to have even more time with it. If I could go back there are things I would change about it. I think it’s a complicated book to read.

Complicated?

Well I imagine that it’s not an easy read. I mean, I don’t know, I haven’t read it, I just wrote it.

Is that what you got from reviews?

Not really. Reviews were generally positive. It could have been shorter, and could have been edited tighter, but I lost my editor at the end.

Well I really enjoyed both your books.

Thank you, I really enjoyed aspects of them and really struggled with other aspects of them, and I’m proud of them both. I’m proud that I did them. I love writing. I’m about to start another book, but I decided that with this one I would not force it out fast, but that I’d think about it, I’d research it and do it kind of like The Fruit Hunters where the first years are not under contract to a publishing house. I think that my timing is that it takes just a few years to think about a book, and then it takes a few years to write it, and so that’s what I decided to do this time.

Are you still figuring out the story?

Yeah, I generally have a pretty good idea of what it is, and I’ve been researching it, but I’m not going to tell you what it’s about, because then it’s going to become a whole 15-minute confused thing. I can’t quite articulate it yet, I’m in the middle of trying to articulate it. I’m trying to write that treatment now. It feels like an exciting project, something I’m excited to do.

And while you are doing that are you doing other things? You’ve been traveling a lot…

Yes, that is how I’ve made my living since The Book of Immortality. I’ve had a good few years as a travel writer. A lot of food and travel writing, that intersection there. And I have managed to be lucky with it, even though I had to work hard and push myself to keep trying to sell ideas. Freelance writing is a different ballgame than writing books. The way it works is that you need to put out a lot of ideas, pitch a lot of ideas and hope that editors will take them. Because of the fact that I’ve done two books, plus my previous journalistic experience, at least editors have been open to hearing the ideas. There’s a lot of ideas I put out that they did not buy, but there’s also been a bunch that have been bought, so I’ve been doing that.

With different magazines?

Yes, I’m a freelance journalist these days, mainly travel writing and food writing. But the kind of food writing I do means there’s almost always travel involved in it. And that seems to have been a big thing that’s also been… to go back to the punk rock thing, the way we were obsessed with punk rock—those same sort of things seems to have happened in the food world. A lot of qualities of the music world have been transposed onto the food world, weirdly. I should mention, because we’re doing this interview for Gravyzine, a few years ago, a musician friend of mine started a food zine here in Montreal called Gravy also. From music to food. It’s like the way people used to be obsessed with 7” singles has happened with eating certain dishes or eating at certain restaurants.

You mean for anybody, or for you?

For a lot of people. A lot of people want to go and “experience” food in the way that a lot of people used to want to go to concerts, it seems to me. People today love food in a way that was totally inconceivable in the 90’s. It may have something to do with the fact that music has become so digital, and immaterial. But at the time when we were into punk rock, the idea that somebody would be into food was unthinkable. There was no such thing as a foodie. To be “into food” was not cool in the least. It wasn’t even conceivable. That outsiderness was in part what attracted me to writing The Fruit Hunters. I remember I went to a magazine store and I saw something called Gourmet magazine and another one called Scientific American. I was like ‘what magazines do normal people buy?’ And I realized that people buy food magazines and science magazines. I found the intersection of those two worlds to be so interesting. I had no idea you could write about food or that you could write about science, and I kinda set out to do both with The Fruit Hunters. But now everybody is so into food, it seems odd to even point it out. Like Instagram is mainly about food. Food has become such a big deal for people. Lives revolve around food.

So it’s sort of a coincidence that you went in that direction?

I just happened to be this guy that ventured down that path a little bit earlier than others. Like now Vice has this food channel called Munchies. In 1999, trust me, nobody in the orbit of Vice was even remotely interested in food. Now the music part of their empire is called Noisy, their news vertical is Vice News, and Vice Food is basically called Munchies. The documentaries I’ve done have mainly been with Munchies.

I read one where you went to Cuba.

Yes, that was a written article for Vice magazine proper, although the assigning editor on that story is the head of Munchies. Actually, that reminds me of an interesting comment I saw recently, when Munchies hired a west coast editor in Los Angeles. He’s this pop-punk East Side Vato Loco Chicano dude. And when they hired him, he was quoted as saying ‘What’s more punk rock than getting paid to write about food?’ I remember thinking: ‘Food writing is not punk rock.’ But then again, the world has changed, and we live in the world now where a young punk rock music lover can also be a food lover and can believe that writing about food is the most punk rock thing that he could possibly do. I don’t exactly agree. I think that most writing about food involves telling people with disposable income how to spend it, unfortunately. But yes, sometimes it can be a way into a culture, into identity, and into bigger questions. And sometimes it can even have political ramifications, or at least political aspirations. I guess ‘punk rock’ can also mean following your own heart, doing what you would most love to do, not letting corporations dictate your path. So I guess, sure, food and travel writing can fall into that category, but with some caveats.

You know that right next to where CBGB used to be there is now a Daniel Boulud restaurant called DBGB? Marky Ramone did a pasta dinner there not too long ago for like $75 a person. And someone recently told me about a pasta dish of malfadine with pink peppercorns that they described as being a “punk rock cacio pepe.” Um, how exactly is a pasta dish “punk rock?” They were like, “It’s different; it has a zing to it; it’s youthful and unexpected.” OK. These days you see concert posters in Brooklyn promoting the fact that there will be “natural gamay” available by the glass.

So what are the best restaurants in Montreal, what would you recommend?

I really like a place called Le Petit Alep near the Jean Talon market. I did a little article about them for Vice actually. [https://munchies.vice.com/en/articles/preserving-the-traditions-of-syrian-swimming-pool-cuisine.] The owners are Syrian, and when they were younger they would spend their summers in Aleppo and hang out at swimming pools. At those Syrian swimming pools, there was food that you could eat poolside. So they opened a restaurant that’s an homage to those dishes you get at swimming pools in Aleppo. I just love the restaurant. And it’s for young people, it’s cheapish, as far as restaurants go. Intentionally, they want it to be a place that’s affordable. They have a more expensive restaurant  that’s called Alep next door that’s more sit down and formal, but the Petit Alep is more casual and cheap and there’s this incredible story behind it. Part of what I love about it is that I always loved eating there, but when I found out that backstory it made me love them even more. They’re an example of how food can sometimes be a way into a culture. Probably the biggest crisis and tragedy of our age has been the civil war in Syria for the past 5 years now, with all the refugees that have spilled over into the rest of the world. It’s the reason Europe is freaking out, Brexit, Trump, all of that… But there goes my tendency to take things too far. My point is: sometimes something as simple as a restaurant can help you make sense of the world. You go there and you learn about what they’re doing and you realize what’s happening in the world today. So I love that place. I go to Le Petit Alep often. I love a place called L’Express, it’s a real Parisian bistro type place. It feels like Paris, but it’s on St-Denis. It’s simple food, it’s not fancy. But it’s French food, bistro food. I don’t know, I often get Banh-mi sandwiches next to the Jean Talon market, at a little place called Marché Hung Phat. It’s $4 for a sandwich. I go there often. There’s a new little taco place that I like called Impact Tacos, 4 tacos for $5. But on Wednesdays it costs $4 for 4 tacos, I think. One of the restaurants that people travel here to experience is Joe Beef and they have a little sister restaurant called Vin Papillion. It’s like a natural wine bar. What’s happening in the world of natural wines is also very similar to punk rock in the sense that there are all these people trying to work their land in an honest way, no bullshit, no chemicals, no preservatives. They’re just trying to get to the true expression of the land. And who knows how it’s even going to get sold and how does it not go off and become all freaky? They’re generally not trying to conform to anything, although of course there are followers and innovators and detractors, just like in the punk world. But the world of natural wines is an interesting one in that it consists of people who are mainly saying fuck the system, let’s do things our own way, let’s do things in the most honest way possible.

that’s called Alep next door that’s more sit down and formal, but the Petit Alep is more casual and cheap and there’s this incredible story behind it. Part of what I love about it is that I always loved eating there, but when I found out that backstory it made me love them even more. They’re an example of how food can sometimes be a way into a culture. Probably the biggest crisis and tragedy of our age has been the civil war in Syria for the past 5 years now, with all the refugees that have spilled over into the rest of the world. It’s the reason Europe is freaking out, Brexit, Trump, all of that… But there goes my tendency to take things too far. My point is: sometimes something as simple as a restaurant can help you make sense of the world. You go there and you learn about what they’re doing and you realize what’s happening in the world today. So I love that place. I go to Le Petit Alep often. I love a place called L’Express, it’s a real Parisian bistro type place. It feels like Paris, but it’s on St-Denis. It’s simple food, it’s not fancy. But it’s French food, bistro food. I don’t know, I often get Banh-mi sandwiches next to the Jean Talon market, at a little place called Marché Hung Phat. It’s $4 for a sandwich. I go there often. There’s a new little taco place that I like called Impact Tacos, 4 tacos for $5. But on Wednesdays it costs $4 for 4 tacos, I think. One of the restaurants that people travel here to experience is Joe Beef and they have a little sister restaurant called Vin Papillion. It’s like a natural wine bar. What’s happening in the world of natural wines is also very similar to punk rock in the sense that there are all these people trying to work their land in an honest way, no bullshit, no chemicals, no preservatives. They’re just trying to get to the true expression of the land. And who knows how it’s even going to get sold and how does it not go off and become all freaky? They’re generally not trying to conform to anything, although of course there are followers and innovators and detractors, just like in the punk world. But the world of natural wines is an interesting one in that it consists of people who are mainly saying fuck the system, let’s do things our own way, let’s do things in the most honest way possible.

So are you writing about that?

I haven’t written too much about that but I love wine, and I find natural wines to be very interesting. It’s a new movement.

Where are the natural wines being made?

Mainly France and Italy. There are some people doing it everywhere though, like in Ontario, California, Republic of Georgia. It’s a grassroots movement in some ways. One of the stories I’ve been interested in is the way that humans first started making wine. Like how did that happen? And why is it that religions are linked to that? Why is wine used when people go to church—why do you drink the blood of Jesus as wine, what is that? Why is that? Something so obvious: what is the reason behind it, how did it come to be? That’s one of the things I started thinking about in The Book of Immortality, within the idea of nature transforming and all of that. It turns out winemaking began at the time when humans stopped being nomadic and settled down into agriculture. It begins near Turkey and Armenia, Iran, the Republic of Georgia, Azerbaijan. That area is where it started, over into Greece and Macedonia. It had to have been somewhere there, all the archeological finds that are like 6000-8000 years old are from that vicinity. And it’s interesting that it is such a war torn region, that it’s always been so contested. ISIS is not far off, the Kurdish peshmerga are right there, Syria’s next door. And the bible says that Noah parked his ark on top of Mount Ararat and planted the first vineyard there. So my interest in natural wine connects to that historical side. There are people who are trying to make wine today like humans first did when they first started making wine. That’s punk rock. That’s like something else; that’s caveman shit. That is primitive in a genuine way. Wines from the Republic of Georgia—there are some really interesting ones. All they do is they dig these holes in the ground and they put these big clay vessels in the ground, so it’s like all you see in a wine making facility there is a hole in the ground. They put all their grapes in there and put a lid on it and that’s it. They just close it and then they come back a year later and it’s like grog, ready to go. They didn’t add anything or do anything, they just drink that. And that’s a real natural wine, in the Republic of Georgia. That’s cool to me, I’m interested in that for sure, I went to do a story there about that, which will hopefully come out soon. And it turns out they found this cave in Armenia, right next to Georgia, that is also crazy. [That story can be read here: http://www.saveur.com/world-oldest-winery-armenia.] I also did another cave-wine story in Crete, actually. It was one of the first stories I did after The Book of Immortality, as part of this travel/food beat I’ve been exploring. There’s a magazine called Lucky Peach, and they were supportive of me at that point. I think the editor realized how precarious my employment status was, and as I was finishing The Book of Immortality he gave me some assignments that helped me get the travel aspect of my writing going. I started by going to  Crete. I ended up in a cave on a mountaintop for a party that these people were having in their village. It was a harvest party where they make their first raki of the year. Do you know what raki is? It’s like grappa, a clear alcohol made with distilled grapes. The villagers were having a raki-making party that night, and as part of the party there was live traditional folk music in the cave. It sounded kind of like the Troggs, but with a lyre-player, and there was this guy playing an Eastern-sounding fiddle over the pulsating rhythms. And all these old people were dancing this weird beautiful slow skeleton dance. I remember thinking that their music is what a lot of punk rock wants to be, like music that is played in a cave on the top of mountain during a harvest party. I found it way more punk rock than the Cro-Mags or any of that stuff that fetishizes the primitive but isn’t really in touch with the past in any way. A true Cro-Mag was just an early human, a Cro-Magnon. And the name Troggs comes from troglodytes, as in those ancient beings who lived in caves. The Troggs were such a foundational early garage rock band, in the way they were reaching out toward some imagined past. In Crete, I felt like I’d ended up in a modern-day version of a cave-using culture that has managed to stay in touch, somehow, with humanity’s earliest roots. [That story can be read here: www.adamgollner.com/file_download/47/crete.pdf.]

Crete. I ended up in a cave on a mountaintop for a party that these people were having in their village. It was a harvest party where they make their first raki of the year. Do you know what raki is? It’s like grappa, a clear alcohol made with distilled grapes. The villagers were having a raki-making party that night, and as part of the party there was live traditional folk music in the cave. It sounded kind of like the Troggs, but with a lyre-player, and there was this guy playing an Eastern-sounding fiddle over the pulsating rhythms. And all these old people were dancing this weird beautiful slow skeleton dance. I remember thinking that their music is what a lot of punk rock wants to be, like music that is played in a cave on the top of mountain during a harvest party. I found it way more punk rock than the Cro-Mags or any of that stuff that fetishizes the primitive but isn’t really in touch with the past in any way. A true Cro-Mag was just an early human, a Cro-Magnon. And the name Troggs comes from troglodytes, as in those ancient beings who lived in caves. The Troggs were such a foundational early garage rock band, in the way they were reaching out toward some imagined past. In Crete, I felt like I’d ended up in a modern-day version of a cave-using culture that has managed to stay in touch, somehow, with humanity’s earliest roots. [That story can be read here: www.adamgollner.com/file_download/47/crete.pdf.]

Were there any scary situations when you were traveling? Are you ever confronted with situations that are uncomfortable?

Yeah, uncomfortable happens often. Scary – infrequently. The situation in the Fruit Hunters, when I went to Cameroon, is fully described in the book. That was a little bit scary, but it was also fun. I had to pay a bunch of bribe money throughout that evening to corrupt members of the military, and that’s never enjoyable.

When writing the Book of Immortality were you often hit with the realization of your own mortality?

Strangely, it’s like when something hurts: if you focus on what it is rather than turning away from it, then it doesn’t really hurt that much. If you are in an experience of pain and you decide to actually just feel the pain, it tends not to be that bad. It’s more our apprehension—the fear of the pain—that is worse. It’s the fear of dying that bothers us but actually dying doesn’t seem to be that bad. I don’t know if that’s a proper answer but that’s what I was thinking throughout much of the writing process. I wasn’t in a terrible state of being afraid of dying.

Did you end up looking at things differently after you wrote that book?

Yeah, definitely. I tried to explain how at the end of the book, I’m not sure I can articulate it now though. I feel that there’s so much we can’t know and we don’t know. I’m grateful I’m not trying to figure that one out anymore.

You’re writing is pretty funny, you have parts that are humorous and witty, so have you always been that way?

I’m a goofball. Somebody I was speaking with recently used the word ‘wacky’ to describe themselves, and I thought, “yeah I’m also kind of wacky too.” I make a lot of bad jokes. I try to see things in a lighthearted way whenever possible, but obviously a lot of comedy comes from a difficult place, sometimes. Many great comedians aren’t the easiest-going people. Like Louis C.K is a hilarious comedian but his comedy is so brutal it is almost self-immolating. But that’s where his humor comes from. I don’t think I’m that brutal a person.

But you notice things…

Being observant, I can’t help it. It’s a blessing and a curse, definitely.

What are some top experiences throughout the course of your writing?

One of the themes throughout this conversation is that, in life as in art, there are a lot of peaks and valleys. Peak experiences: you have to enjoy them while they last. It’s brief. For example, it was really fun to go to David Copperfield’s private island. Leaving the island was a real great feeling, having been there and being on the way home with my friend, I remember I couldn’t stop laughing. There are great moments when you laugh, but that’s not to say that moments that are more emotionally complicated are not just as valid. In fact, they’re often more powerful. Experiences at the bottom are also important and I’m grateful for those times as well. Those often are where this all comes from. I don’t want to just run away from those things, I want to allow them to be as real as the moments of joy and pleasure.

So what are you listening to these days?

Let’s see… (We walk over to Adam’s record collection and he rifles through his albums.) Well I’ve been loving John Fahey, this guitar player. He’s unbelievable. The Pagans, I still love “Street Where Nobody Lives”, and “Eyes of Satan” is really fun to listen to. I put this on recently – The Best of Sam Cooke — he’s the best. And Francoise Hardy, of course. I’ve been really liking this German music that happened maybe around the same time in the 1970s that punk rock was happening, I guess sometimes they call it Krautrock or Komische music, but there’s a bunch of that stuff that I’ve been really loving, particularly Edgar Froese and Cluster. There’s an album by Cluster with Brian Eno that is like, whoa what is this music? One of the musicians in Cluster was named Roedelius, and some their records are done at like the exact same time as punk rock stuff in 1976, 77, 78, but it was of course a very different scene. I have an album where Iggy Pop and David Bowie thank Roedelius, or the other way around, so they were aware of each other…

So you listen to a lot of old stuff.

Yeah, mainly what I do is go through these records I accumulated in my twenties.

And now you are rediscovering them.

Yeah, it’s a library here. Thank you Adam, age 25. This a new album: Joanna Newsom, Divers. Do you know her?

No.

It’s not punk rock, it’s like harp music. It’s no Alice Coltrane, but it’s pretty powerful.

Where do you buy your records from?

When I buy new music, which is pretty rarely, I go to Phonopolis on Bernard cause it’s just down the street. There’s also that store on St. Denis and Pine, Disques Beatnik, but I don’t go very often, I went record shopping like maybe two times last year and no times this year. I also have all this stuff that I don’t really listen to so I’m trying to go through it and listen to it all. Oh I really love Jonathan Richman, too.

Oh, of course.

Always. Blues – I’ve been listening to some good blues, do you know a guy named Junior Kimbrough? He was from Mississippi, not the Delta, the hill country, near Oxford, he has this album, I think it’s called All Night Long, but it’s amazing, check out the song “Meet Me in the City.” It’s crazy that he was doing stuff at the same time as The Spaceshits. I remember seeing R.L. Burnside in Montreal in the 90s. He was like “I drink Bud cuz it makes you wiser.” And I just saw his grandson Cedric Burnside play an amazing concert in Clarksdale, Mississippi a few months ago.

So just changing topics from music to fruit: after The Fruit Hunters, what’s the tastiest fruit you tried or your favorite fruit?

So just changing topics from music to fruit: after The Fruit Hunters, what’s the tastiest fruit you tried or your favorite fruit?

I really like this thing called the ice cream bean which is from Ecuador in the Amazon, somewhere around there. It’s like a really long thick green bean almost the size of a baseball bat, just a little smaller, and you open it and it’s got all this cotton candy type fluffy stuff inside of it. They say it takes like vanilla ice-cream diffused through cotton candy-like veins. Like the cream is inside the filaments of the fruit’s cloud-like substance. You bite into it and it’s got the sensation of having vanilla ice cream in it, somehow. It’s a bit weird, and you have to get it at the peak of ripeness for it to really taste right. I also really enjoy a good pear. Yellow kiwis are a fruit I like. Have you ever had a yellow kiwi? They’re kind of around, in stores. They’re a good fruit.

Can you get them at the Jean-Talon market?

Yeah, you can get them there at a place called Chez Nino. A yellow-fleshed kiwi. I think it costs like a buck twenty-five a kiwi, but it’s worth it. You cut it in half and eat it with a spoon. It’s great.

You don’t eat the skin?

No. I also like honeycrisp apples a lot. A good honeycrisp from Quebec is pretty good.

I had some good macintosh apples recently. They were very red, like rosy red, and the inside was also like veins of red. They were so good…

That’s great, I love that feeling.

So do you think that one day we will be a society of cyborgs, do you think that’s actually possible?

I guess it’s possible; anything’s possible. I hope we won’t be, I definitely don’t know. Who could have predicted the Internet? Cyborgs, god, I hope not. I don’t want to be a machine. I like real things.

So The Fruit Hunters movie, Bill Pullman, is he playing you?

So The Fruit Hunters movie, Bill Pullman, is he playing you?

It’s interesting, but he’s only in the movie a bit, right? He’s not there throughout. So I don’t think he’s playing me. He’s playing himself. Bill also loves fruits, he’s a fruit lover. The documentary is its own thing. But I will say that when I met Bill the first time, I had the sensation that he was an actor who was trying to figure out what I’m like, in order to get into the role. He was sort of scrutinizing me, in a friendly, professional thespian way. I remember he did this amazing thing in real life that he also does in Independence Day. You know when he’s the president, and he kind of gives the thumb’s up to everyone in that movie? He does that in real life too. And after meeting him, I ended up doing it too, giving that presidential thumbs up to people. I enjoyed that transference. Bill is so funny, a real sweet and genuine person.